The Highest Paying States for Guidance Counselors

While most commonly associated with providing assistance in college or [...]

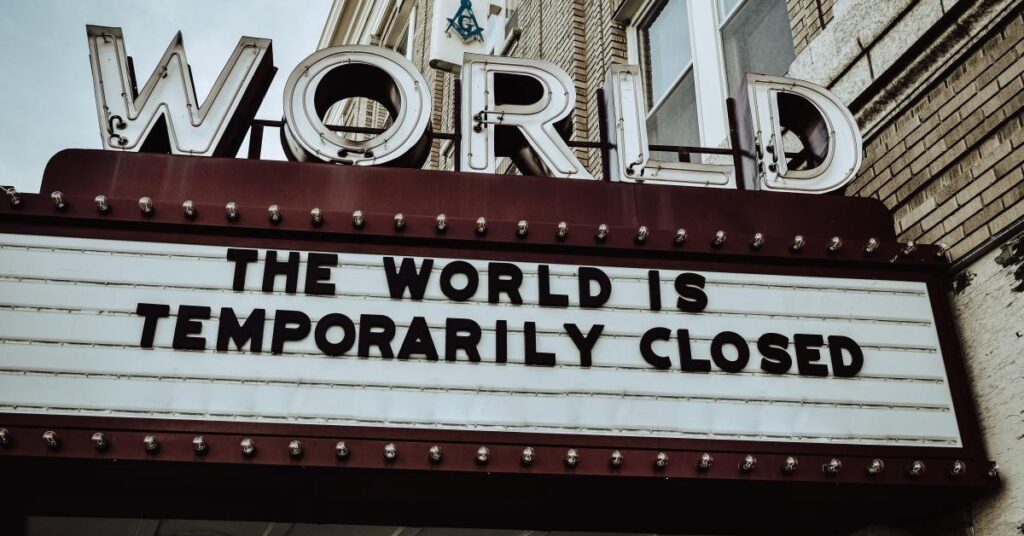

Policing has always been an uncomfortable fit with mental health and domestic crises, but calamitous recent events have pushed this persistent issue to center stage. Tragic shootings are just the most prominent examples of what goes wrong when police approaches supplant mediation, mitigation, counseling, and other social work solutions. All-too-frequent police failures to de-escalate confrontations have led to public calls to “defund the police.”

What many advocates seek, in fact, is not the abolition of police forces (an approach the term “defund” inaccurately suggests) but rather a shift of funding and approaches toward more effective, less lethal responses. These include embedding social workers with law enforcement on calls where appropriate, where the careful consideration of social conditions and psychological factors can mitigate otherwise potentially lethal confrontations.

The question is: can social workers and police officers coexist in a blended workforce?

A social worker’s job description can involve de-escalating and remediating mental health crises, manic episodes, or domestic disputes through crisis intervention and conflict resolution skills. Furthermore, trained professionals, such as licensed clinical social workers (LCSW), treat mental, behavioral, and emotional disorders, provide treatment plans, and follow-up to evaluate their effectiveness. They also:

On the other hand, law enforcement officers serve as first responders to emergency and non-emergency calls with an oath to protect and serve lives and property. Typical job functions include:

The job functions of a social worker and police officer barely cross paths except for one distinct area: serving as a first responder. Police officers respond to calls regarding criminal activities, while social workers respond to calls regarding mental health emergencies and other behavioral concerns. But what happens when those calls overlap? Could a specialization in police social work become a new career path?

This article will discuss the emerging trend of social workers in police departments and also addresses:

Increased public awareness of lethal encounters between police and citizens has led to calls to reimagine policing. A shift in resources could facilitate the inclusion of social workers in place of (or in tandem with) law enforcement for non-violent or non-criminal emergencies.

In fact, some police departments have already implemented such collaborations. The Eugene Police Department works with a mobile crisis intervention team called CAHOOTS (Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets), funded by the city through the department. Instead of sending police officers, the team sends a unit that includes a paramedic and an experienced crisis social worker dispatched through the 911 call center or the city’s non-emergency number. CAHOOTS’ longevity—the program is 30 years old—attests to its effectiveness.

High-profile deaths at the hands of police, including those of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor in 2020 at the hands of police, have given rise to newer efforts. So too has the use of excessive force that led to the fatalities of victims experiencing a mental health crisis; Elijah McClain of Aurora, Colorado and Daniel Prude of Rochester, New York are among the most prominent examples. These tragedies sparked an outcry to dismantle racist policing and reallocate police department budgets to mental health professionals who can mediate rather than escalate situations.

In 2021, the Alternative Response Pilot Program in Columbus, Ohio, launched a “Triage Pod” consisting of a social worker, emergency communications dispatcher, and a paramedic to address substance abuse, mental health emergencies, and other behavioral health issues rather than sending law enforcement. The part-time pilot program determined that 48 percent of calls received were non-emergencies that could be resolved by the dispatcher or redirected to appropriate community resources.

Similar pilot program initiatives began to emerge over the last year, such as:

Social work solutions save lives and improve public safety while reducing strain on local communities’ overtaxed criminal justice systems. While a small percentage of non-emergency calls may require backup from law enforcement, most calls diverted to crisis teams deliver the necessary mental health services or immediate treatment without the use of force or firearms.

| University and Program Name | Learn More |

|

Virginia Commonwealth University:

Online Master of Social Work

|

Consider this scenario. A child has a mental health crisis in school and acts out. Should the teacher call the police to intervene or contact their social worker?

Social workers deploy crisis intervention techniques and likely have an established history with the student. In addition, social workers keep accurate records of their clients, alerting them to what triggering event may have caused a shift in mood or behavior. Police, in contrast, may not be sufficiently trained to identify mental, emotional, or behavioral disorders which may cause the situation to escalate.

Most law enforcement academy training focuses roughly 80 percent of its time on crime-fighting functions dealing with homicides and robberies. The other 20 percent may include service-related tasks involving crisis intervention or referrals. Mental health professionals—primarily licensed practitioners—have years of education, often requiring a Master of Social Work (MSW), field placement, and proper licensures and credentials.

With two vastly different skills and requirements, it’s quite clear that trained social workers have the more appropriate skill set to manage mental health situations. Additional services trained social workers can provide within policing include:

Social workers carry unique skills and competencies that prepare them to handle non-emergency threats. They can diffuse many situations without the need to engage law enforcement.

The National Association of Social Workers (NASW) released a social justice brief that included innovative approaches to 911 emergency responses and collaborative partnerships with law enforcement agencies. While some police departments around the country are growing more receptive to embedding social workers within law enforcement, others aren’t so sure it’s the right move.

One side of the argument suggests keeping the two fields separate. One article asserts that “attempting to do social work while a police officer hovers nearby would be counterproductive and emotionally violent.” It also states that the presence of police and the risk of excessive force heightens anxiety, making it harder for social workers to perform an already challenging job.

Another opposing position notes that although police officers may not have crisis intervention or negotiation skills, social workers don’t have the tactical skills to manage an individual who has a weapon or poses potential harm to others. In this instance, the social worker, who typically arrives unarmed and without protective gear in a civilian car, is potentially at risk.

Social workers undoubtedly face risks, regardless of whether they work in tandem with police or independently. However, as calls related to mental or behavioral health issues continue to flood 911 call centers, finding better resolutions is critical. Training emergency communication dispatchers represents another area of potential improvement. Many civilians only know to dial 911, which then requires training for dispatchers to know who to send to the scene. Some dispatchers send crisis intervention teams as first responders, while others send police first to ensure it’s safe for social workers to arrive as “follow-up.”

Whether social workers or police officers act as first responders varies based on safety concerns and available community resources. Social workers aim to assist individuals and communities in need where dialing 911 in case of emergency shouldn’t be their first resort.

Social work practice consists of advocacy and case management. Social workers serve as resources, counselors, therapists, and much more. A bachelor’s degree in social work teaches the necessary skills for entry- and mid-level jobs. However, an MSW prepares social work professionals for positions that address societal roots affecting equal access to resources. An MSW is also a prerequisite for licensed practitioners who properly diagnose and provide treatment plans to patients experiencing mental illnesses.

Online MSW programs like the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Social Work include curricula on inclusivity, cultural competence, promoting social justice, and developing human relationships, all essential if providing training or collaborating with law enforcement. Likewise, the Tulane University School of Social Work offers an opportunity for students to supplement their MSW with a certificate in Mental Health, Addictions, and the Family, or Disaster and Collective Trauma, to learn different crisis intervention and treatment approaches.

Whether social workers function in place of, in tandem with, or remain siloed from law enforcement, the continued conversation and implementation of alternative response options prove there is a need to strike a balance.

Questions or feedback? Email editor@noodle.com

While most commonly associated with providing assistance in college or [...]

Certifications certainly boost one's resume, demonstrating advanced proficiency in a [...]

Whether handling case management in homeless shelters, working as mental [...]

Social workers toiled heroically to deliver relief in the face [...]

Dual degree programs still represent a significant commitment, but those [...]

Categorized as: Emergency Management, Social Work, Social Work & Counseling & Psychology