What Is the Epidemiological Triangle?

The epidemiological triad or triangle is an organized methodology used [...]

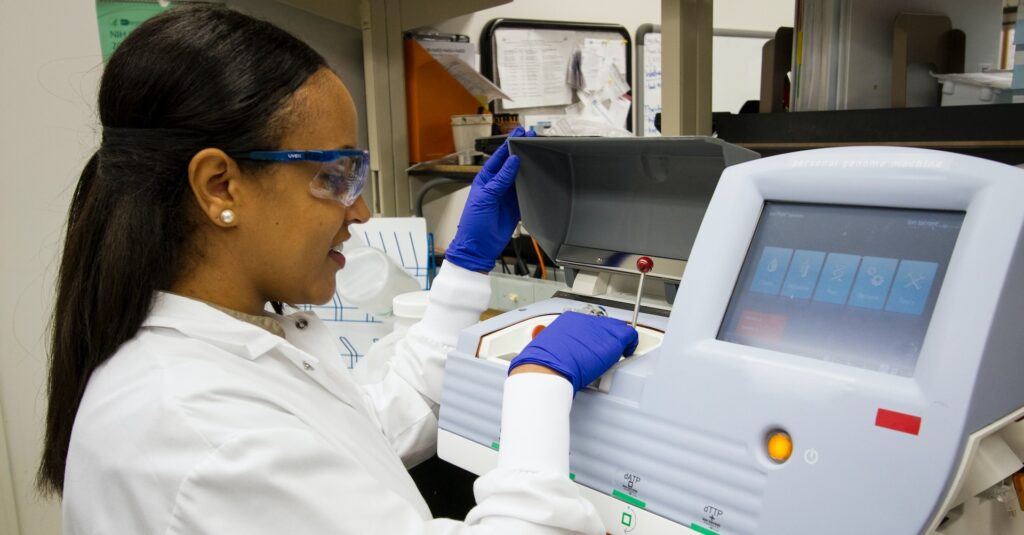

Not all doctors see patients. Pathologists are technically direct care providers, but they generally don’t interact with their patients. Instead, they’re down in the lab, analyzing samples and test results, making diagnoses, and shaping and refining treatment plans.

What pathologists do is largely invisible to patients, but there’s a good reason these medical specialists are sometimes called ‘the doctor’s doctor.’ Labs in hospitals, standalone diagnostic testing facilities, medical schools, government agencies, pharmaceutical companies, and research organizations are open 24/7, and their continuous operation is part of what lets patient-facing doctors and specialists do what they do.

Becoming a pathologist is a great option for anyone who wants to get into medicine and is fascinated by what actually happens to our blood, bodily fluids, organs, and other tissues when we get sick. You’ll be a vital part of your patients’ care teams, but your work will be primarily analytical. Ready to learn more about this well-paying career?

In this article we’ll cover:

The New York University Langone Health Department of Pathology describes pathology as the branch of medical science concerned with the “general study of disease and its processes as well as the specific diagnosis of disease,” adding that pathologists “investigate the clues to diseases and injuries through the examination of organs, tissues, body fluids, cells, and molecules.” Simply put, it is an empirical, observation- and test-driven approach to medicine. Illnesses and diseases leave their mark on the body—physically and chemically—and pathology uses these markers as a diagnostic tool.

Pathologists are puzzle solvers. They’re medical doctors who work in laboratories studying and testing tissue and fluid samples to diagnose patient conditions and recommend treatment options. Instead of working with patients, they work closely with primary care physicians, surgeons, and other medical professionals who treat patients directly.

Some pathologists work under laboratory directors and some are laboratory directors. Many oversee the work of laboratory medicine scientists, medical technologists, and clinical laboratory scientists.

When you become a pathologist, you’ll probably spend the majority of your time in the lab, analyzing samples by making observations and performing tests to identify or rule out diseases and conditions. You won’t work in a vacuum, however. You’ll need to be a great communicator, not just a great investigator, to succeed in a pathology career because having an analytical mind isn’t enough.

On any given day, you’ll also have to listen carefully as doctors describe patient symptoms and medical histories, and you’ll have to convey information clearly as you outline test results and treatment options for physicians and surgeons.

A typical week for a pathologist might include:

There are many types of pathology careers, and pathologists work in all areas of clinical medicine. Many people associate the term pathology with forensic science and the medical examiner’s office, but forensic pathology is just one of the specialties in this fascinating field that tends to attract problem solvers and mystery lovers.

The two main branches of pathology are anatomical and clinical pathology.

These aren’t the only kinds of pathology careers. There is also cytopathology, which is mainly concerned with examining bodily fluids at the cellular level. Neuropathologists are experts at diagnosing diseases of the central nervous system. Pathologists who specialize in transfusion medicine make sure that the blood in blood banks is safe.

All aspiring doctors begin their educational journeys by choosing a four-year bachelor’s degree program. There are no specific pre-med bachelor degree programs, but most medical schools require applicants to have taken certain science, math, and English courses to be eligible for admission. These usually include microbiology, physics, biochemistry, human anatomy, and calculus, though every medical school will have its own admissions criteria—which usually begins with a GPA of 3.5 or above and a great MCAT score. Medical school admissions are tough, so it pays to do everything you can to make yourself an attractive candidate as early as possible.

If you’re sure you want to become a pathologist, then you can increase your chances of being accepted into medical school by majoring in biology or chemistry at a university with a strong pre-med support program. These schools typically have mentorship and advisement, tutoring, and research and clinical opportunities lined up for their pre-med track students.

Future doctors attending the University of Washington, for instance, are assigned pre-health career coaches that help students choose classes, find job shadowing opportunities and point them toward resources for becoming a doctor. Students at Duke University work closely with an advisor who walks them through the medical school application process.

Your next stop on your journey to becoming a pathologist will be attending four years of medical school. Choosing the best medical school for pathology education is largely a matter of identifying which schools match their students into pathology residencies most frequently.

These schools had the most residency matches in 2018:

Your first two years as a medical student will involve a lot of classroom learning focused on topics like anatomy, immunology, biochemistry, genetics, pharmacology, and infectious diseases. In years three and four of medical school, you’ll start treating patients under the supervision of licensed GPs, psychiatrists, neurologists, surgeons, and specialists in other areas.

Finishing four years of medical school doesn’t mean you’re a doctor, much less a pathologist. The educational commitment to become a pathologist is long and involved.

Next up, you’ll match into and complete a three-year or four-year residency program. This is when you’ll dive deep into clinical pathology or anatomic pathology. Some residency programs cover both. You’ll take part in rotations at hospitals and medical laboratories, and possibly also work on research projects. The hours will be long, and burnout rates may be as high as 52.5%, but you will learn more than you ever thought possible about pathology and make important networking contacts in the process.

Like all doctors, you’ll earn your medical license by going to medical school and passing the USMLE. In some states, you’ll also need to pass a background check and show an understanding of medical law and ethics. You’ll actually begin the process of applying for your medical license during your residency.

The certification process for pathologists may also begin during your residency. Not all, but most pathologists are board certified through the American Society for Clinical Pathology (ASCP) in clinical and/or anatomical pathology or via the American Board of Pathology (ABP) in clinical pathology.

There are also further accreditation and subspecialty certifications in areas like cytopathology, chemical pathology, transfusion pathology, hematology, pediatric pathology, and neuropathology—most of which will require one-year fellowship training in addition to your residency. ASCP certification lasts for ten years, during which period a pathologist is required to participate in continued medical education and show evidence of successful performance evaluations.

A 2019 Medscape survey found that the average pay for pathologists in the US is approximately $308,000. Obviously, an individual pathologist’s pay rate will depend on their level of experience, specialty area, education, location, and industry, but you won’t go hungry when you choose this career.

You’ll also be very employable. CareerExplorer gives pathologists an A– employability rating, which means there will be plenty of employment opportunities for the foreseeable future.

There will probably always be a demand for pathologists. You can’t automate every part of the diagnostic process and there will always be illness and diseases. Pathology is one of the foundations of medicine, which means this career is here to stay.

Most medical professionals have to specialize in an organ or a disease. Pathologists work with doctors and surgeons across many specialties.

Cancer Research UK interviewed Dr. Suzy Lishman, President of the Royal College of Pathologists for its blog, and when the organization asked her what she would change about the field, she said: “I’ve never worked in a hospital where the department of pathology wasn’t hidden away, often with few signs indicating its location…my wish would be for all pathology departments to be in a prominent position in the hospital so that patients and healthcare professionals can come to the department to talk to the pathologists and scientists who work there, discuss results, and find out more about how the specialty contributes to everyone’s care.”

So, is pathology the right career for you? Consider your motivations for becoming a pathologist. Journalist H. L. Mencken summed up what he believed drove most pathologists thusly: “What actually moves him is his unquenchable curiosity—his boundless, almost pathological thirst to penetrate the unknown, to uncover the secret, to find out what has not been found out before.” That’s not a bad reason to embark upon a pathology career, actually. And if you save some lives along the way, all the better.

(Updated on January 24, 2024)

(Last Updated on February 26, 2024)

Questions or feedback? Email editor@noodle.com

The epidemiological triad or triangle is an organized methodology used [...]

A family nurse practitioner (FNP) provides comprehensive primary health care [...]

FNPs practice in a broad range of health care settings. [...]

Some epidemiologists assist pharmaceutical companies in developing safer medicines. Some [...]

Certifications certainly boost one's resume, demonstrating advanced proficiency in a [...]

Categorized as: Medicine, Nursing & Healthcare