Boost Your Teacher's Salary with a Master's Degree

Even in states where a master's degree isn't required, teachers [...]

If you’re the parent of a child with disabilities, your first consideration when adjusting to a new school should be her special education teacher. An educator who is trained in evidence-based practices for students with special needs will be well-positioned to give your child a top-notch learning experience.

Unfortunately, the field of special education continues to suffer from an inadequate supply of teachers who are specifically trained to work with students with disabilities. In addition, even teachers who receive such training last an average of 2.5 years in the classroom. In an ideal world, teacher preparation programs (TPPs) would be graduating well-prepared, highly qualified special education teachers by the dozens each year — but this isn’t the case.

As a parent, what do you need to know about the training your child’s teacher has received? Moreover, what can you do to advocate for improvements to the field of special education training?

The training that special education teachers go through varies from state to state, from district to district, and often from school to school. Typically, special education candidates attend similar teacher preparation programs as prospective general education teachers, but the coursework and field experience differ in important ways.

Classes in a special education TPP usually include topics that are unique to this field: how to teach math and reading to students with disabilities , how to plan for and assess these learners, and how to incorporate Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and assistive technology into the classroom. Moreover, these candidates complete hours of field experience in a special education classroom so that they make the theory-to-practice connections necessary to become effective teachers for students with special needs.

Often, special education teacher candidates also seek general education certifications, enabling them to teach in either setting — special ed or mainstream — at the end of their undergraduate programs. In such dual-certification cases, these students will complete fieldwork in both types of classes. The following overview broadly describes the paths prospective special ed teachers follow, but the reality is that there is so much more our schools of education could be doing to train candidates for this essential and demanding field.

In an ideal world, what recommendations would I make to ensure our TPPs are preparing the highest quality special educators for every state? And how does these compare to current TPP practices today?

A special education candidate will complete all of her coursework — focusing specifically on best practices for students with disabilities — before she begins her final internship and student teaching. Throughout these classes, she will have several opportunities to spend time in special education settings, practicing what she’s learned in her program.

Many undergraduates who decide to go into special education seek dual certification in general education as well — which means that they are pursuing two sets of requirements in the same duration that their general education peers are completing one. While this may sound efficient, it is an exhausting process. Dual-certification candidates must take twice the number of courses, complete two times as many field experience hours, and work with double the number of professors and supervisors as classmates seeking a single certification — all within a typical four-year undergraduate program.

Moreover, because of the general time restrictions of undergraduate programs, special education candidates can only receive one course in formal special education assessment procedures. In a 16-week semester, that is, they must learn, apply, and comprehend all elements of the formal special education evaluation process — a vast and difficult area of study. (Keep in mind, too, that formal assessment is one of the main jobs of the special education teacher.)

Students in special ed TPPs will spend one full semester as interns in a special education classroom, observing the practices of experienced teachers. In addition, they will devote an entire semester to student teaching so they can apply their learning under the supervision of seasoned educators.

Many special education TPPs require candidates to complete one year’s worth of student teaching in a semester’s timeframe. Students who are earning two certifications must fulfill student-teaching responsibilities in both classroom settings. While single-certification peers are permitted two full semesters in one class, their dual-certified classmates are only accorded one semester in each of two classroom settings. The consequence of this structure is that they must learn and practice the skills of a full-time teacher over the course of a single 16-week semester for each certification.

In the TPP in which I work, moreover, our students are still completing the rest of their undergraduate requirements during their internship semester, and this schedule can be particularly demanding for dual-certification candidates who often take up to five classes while simultaneously fulfilling their internships. As a consequence, they are only able to spend three days per week in the classroom, rather than five like their single-certification peers. Because they cannot practice in a classroom five days each week and they only have time to spend one semester in each type of setting, their practical experience is further limited.

Extend dual-certification programs to five years to provide students with the opportunity to get an entire year of student-teaching in both a general education and a special education classroom.

In five-year programs, ensure that all coursework is completed before students begin student-teaching by opening up summer courses to fulfill requirements or earn other credits.

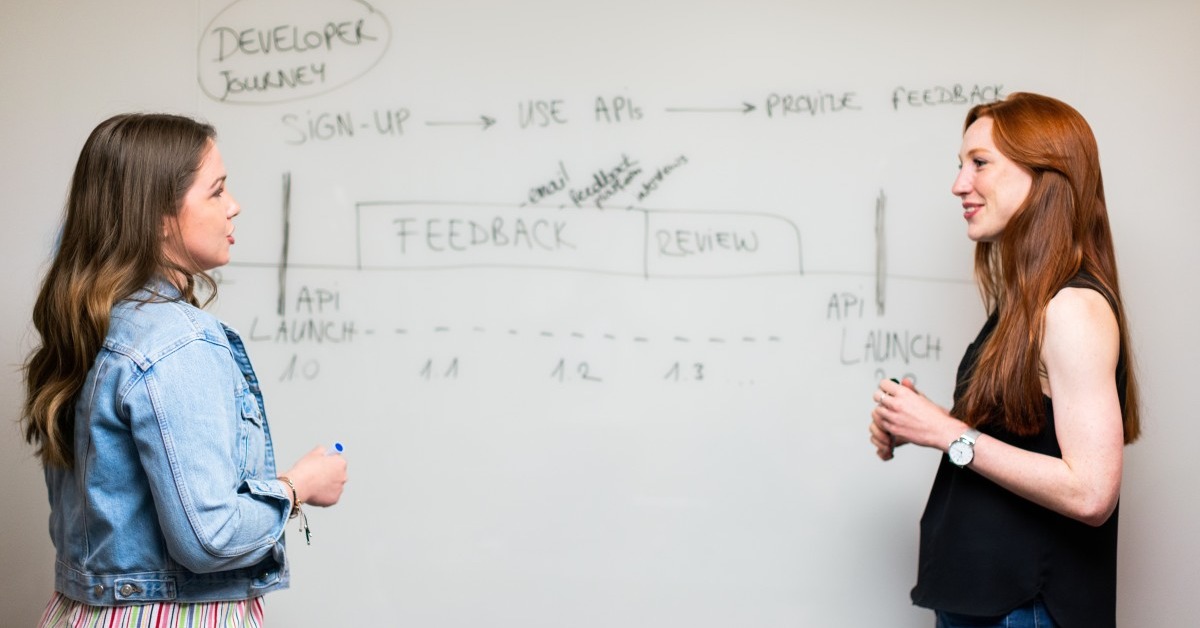

Each candidate will have an active and thorough university supervisor who observes her teaching, provides constructive feedback, and supports her in making the theory-to-practice connection in the classroom.

University faculty have specific percentages of their workload that are dedicated to various responsibilities, such as research or teaching. At a research-focused institution, supervising teacher candidates may represent a smaller percentage of a faculty member’s workload than at other universities. Accordingly, fewer hours will be dedicated to this responsibility on a weekly basis.

Without specific standards for this oversight, candidates’ experiences with their supervisors can vary greatly. There are those who are deeply engaged, observing students in the classroom each week and providing regular feedback. But there are many supervisors who visit once or twice a semester for formal evaluations, but otherwise provide little or no additional guidance.

| University and Program Name | Learn More |

|

Merrimack College:

Master of Education in Teacher Education

|

Ideally, the teacher who works with your child will be certified in special education, at a minimum. This may sound like an obvious prerequisite for such a position, but about 11 percent of current special education teachers are underqualified. Moreover, upwards of 98 percent of districts have reported unfilled special education positions within their schools. As a result of such realities, teachers are often hired to fill these roles without specific credentials in the field.

When you visit schools, you may want to ask about the classroom educator’s area of expertise. For example, if your child has severe autism and is likely to spend most of her day in an extended resource-room setting, you will want the comfort of knowing that her teacher is specifically trained in autism spectrum disorders, severe disabilities, and the best instructional practices for students with these functional and cognitive challenges.

That said, it’s important to begin the relationship with your child’s teacher on a positive note. There are highly-trained special educators out there who make a great difference in the academic life of students with disabilities, as well as newly certified teachers with fewer credentials and less experience who are just as devoted to providing meaningful educational experiences to their students.

When you become familiar with the special education team in your child’s school, you can offer to be an advocate for these educators, as well as for your child. You can petition local elected officials for district-provided supports, federal and state funding, and high-quality teacher preparation programs. Or you can ask your child’s guidance counselor about disability advocacy groups and become involved to create an impact at the national level through letter-writing campaigns, gatherings, and testimonials.

Be a voice for your child and her teacher!

*Find more expert advice from Lisa Beymer, including responses to questions posed by other Noodle readers and other articles about special needs.

Sources:

HQT status of teachers employed to provide special education in U.S. and outlying areas. (2008, July 15). Retrieved September 30, 2015, from U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs

McLeskey, J., Tyler, N., & Flippin, S. S. (2004). The supply of and demand for special education teachers: A review of research regarding the nature of the chronic shortage of special education teachers. The Journal of Special Education, 38(1), 5-21.

Questions or feedback? Email editor@noodle.com

Even in states where a master's degree isn't required, teachers [...]

Getting an MAT or an MEd in Elementary Ed can [...]

As a math teacher, you may qualify for higher pay [...]

According to Zippa, salaries for school principals range from under [...]

Some kindergarten teachers earn $98,000 a year. That likely won't [...]

Categorized as: Special Education, Education & Teaching