Where Do Epidemiologists Work?

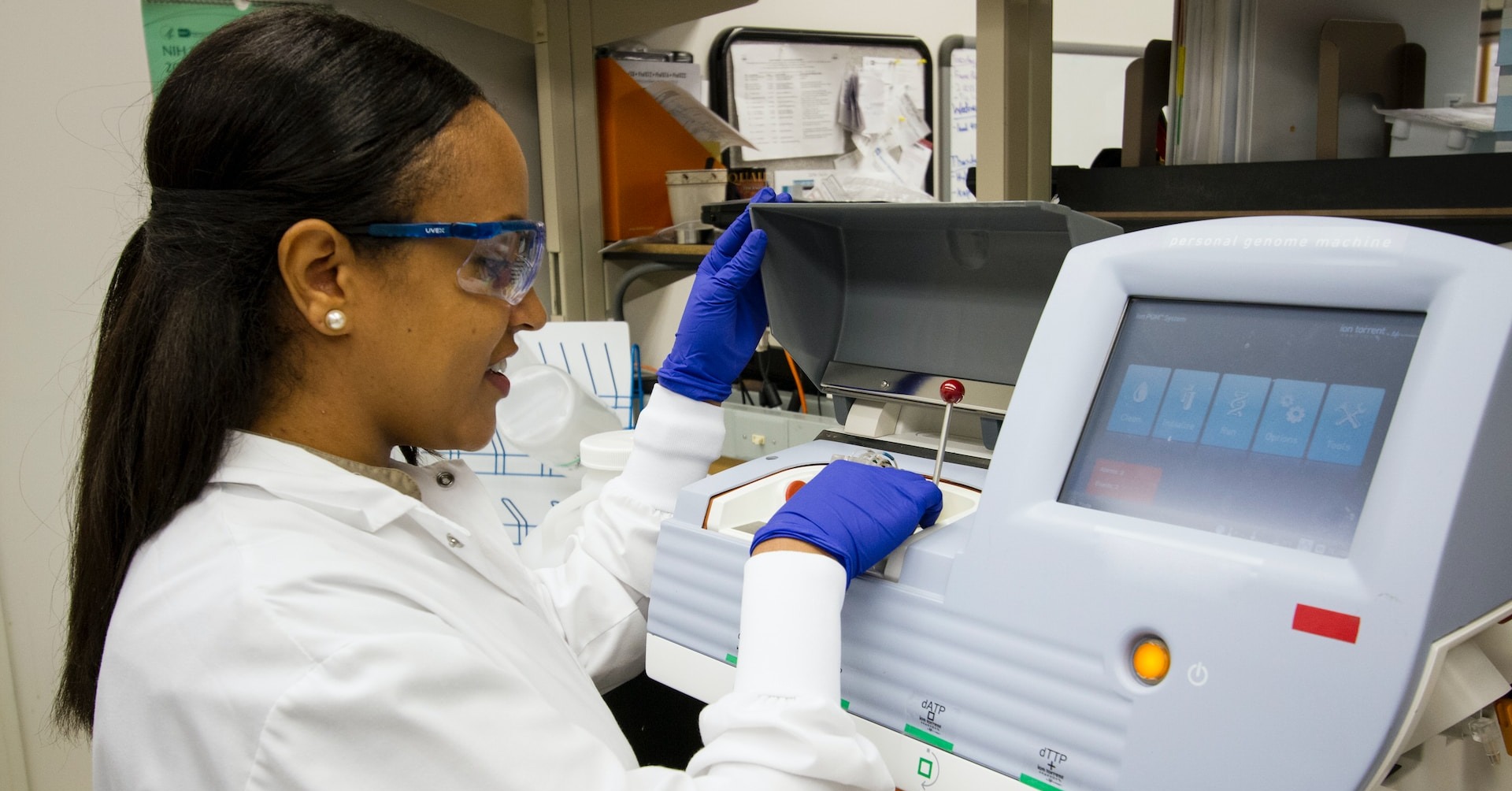

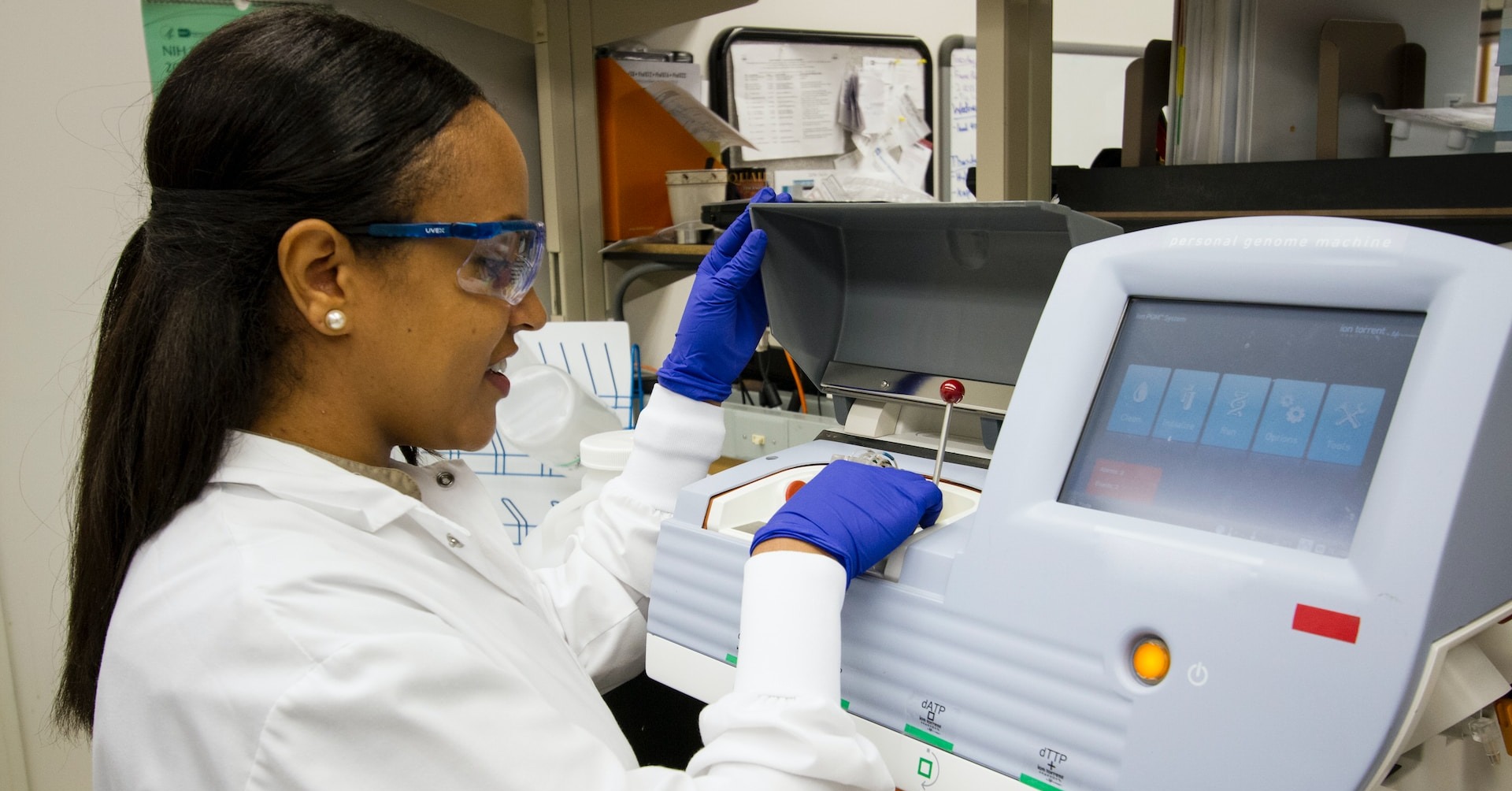

Epidemiologists work in many settings, including hospitals, universities, and federal, [...]

If you’re a prospective or current physical therapist, 2020 is a big year for you. No, not because it’s a leap year—although, yay, one extra day of PT! And no, not because presidential election years result in knottier backs and rage-induced injuries requiring PT.

It’s because 2020 is the year the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) decreed the deadline by which “physical therapy will be provided by physical therapists who are doctors of physical therapy.” Until 2020, a Master of Physical Therapy (MPT) or a Master of Science in Physical Therapy (MSPT) was sufficient to practice physical therapy. However, advances in the field have required practitioners to develop doctoral-level knowledge and skills. Accordingly, the new prerequisite for PTs is a Doctorate in Physical Therapy (DPT).

This more rigorous credential requires more education and more training, which in turn means that the need for physical therapy professors might also increase. If you’ve been thinking about entering the physical therapy teaching profession at the college or university level, now might be a good time to make your move. To do that, you’ll need to know how to become a physical therapy professor. This article tells you. It covers:

A physical therapy professor teaches physical therapy at the undergraduate and graduate levels. They are themselves physical therapists, many of whom continue to practice as they teach. Some have retired from practice but continue to teach and, perhaps, conduct research. In addition to teaching, a physical therapy professor may also advise and mentor students and serve on committees.

A physical therapy professor’s responsibilities include:

Very few physical therapy professors can teach across the curriculum of a doctoral program. Most specialize in one or more areas. Job postings for faculty typically seek applicants able to teach two or more practice areas. These specializations include:

The American Board of Physical Therapy Specialties confers certification in many areas of specialization. Most employers of faculty will expect candidates who claim specialization to hold the appropriate certifications.

Like most organizations, academic institutions are hierarchically organized. As you doubtless know from past experience as a student and perhaps as a teacher, not all professors enjoy the same status. There are professors, and there are professors-you-do-not-mess-with. Within the hierarchy of academia, faculty enjoy more-formal titles. These include:

To teach physical therapy at the college or university level, you will likely need a terminal degree. In rare instances, schools will hire faculty members with master’s degrees, but such hires are typically temporary stopgaps to fill an urgent need. Furthermore, most institutions require faculty to hold an academic doctoral degree—a Doctor of Physical Therapy, which is a professional degree, usually isn’t enough.

Most physical therapy professors hold one of the following degrees.

Unlike the DPT, which trains physical therapists to work with patients, a PhD in physical therapy trains researchers and educators. Whereas DPT students learn and practice established techniques, PhD candidates are more likely to explore new experimental treatments and approaches. Students spend much of their time developing expertise in a specified subject and conducting research into that subject (i.e., a dissertation). Most candidates already hold a DPT, although some may hold a master’s in a related field and a bachelor’s degree in physical therapy. Schools offering a PhD in physical therapy include:

The DSc/ScD degree straddles the line between the professional-practical DPT and the academic PhD. As with a PhD, original research is an essential component of earning a DSc, but the DSc may also include advanced training in specialized practice. The goal of such programs, according to Drexel University, is to prepare students “to take leadership roles as educators and master clinicians in rehabilitation sciences.” A DSc typically takes three to five years to complete. Schools offering this degree include:

A Doctor of Education (EdD) degree prepares candidates for leadership roles in education, not in physical therapy. In combination with a DPT, however, the EdD is often enough to qualify therapists to teach physical therapy at the university level. The EdD theoretically confers expertise in teaching, something that, sadly, cannot be claimed by all PhDs. That’s why many job postings for PT professorships include the EdD among the qualifying degrees.

As previously mentioned, a DPT on its own likely will not qualify you for a professorship. It is almost certainly a degree you will need, however. It is now the required degree to practice physical therapy, and who wants to be taught PT by someone who has never practiced? You will likely need to supplement your DPT with another advanced degree (such as one of the degrees listed above) to procure a teaching position. A number of schools offer combined DPT/PhD dual degree programs, including:

If all this seems a little daunting, remember that there are options other than teaching PT at the undergraduate or graduate level. You could teach community groups or you could teach in continuing education programs with nothing more than your DPT. You may even land a job as an instructor at your local community college. If your goal is simply to teach people interested in physical therapy, there are faster ways to achieve it than by earning a challenging, costly, and time-consuming doctorate.

Teaching at the university level can be a thrilling experience. It’s not without its challenges, however. As political scientist Wallace Stanley Sayer once observed, “The politics of the university are so intense because the stakes are so low.” If you can deal with the occasional petty squabble or turf war, however, it can be a pretty good way to earn a living. Here are some of the pros and cons of the job:

If you’re asking this question, chances are you are currently a practicing physical therapist looking to change things up in your career. If you have the urge and skills to teach, and you have a terminal academic degree in a related field—or are willing to put in the time, effort, and expense to get one—then becoming a physical therapy professor is certainly an option worth considering. The final questions you need to ask are: where will the jobs be when you’re ready to apply? And, will be willing to relocate if necessary?

If your answers are yes across the board, then maybe you should give it a shot. What have you got to lose? You’ll still have the skills to practice physical therapy, so even in a worst-case scenario, you’re no worse off than you were before. That’s an advantageous position to be in.

Questions or feedback? Email editor@noodle.com

Epidemiologists work in many settings, including hospitals, universities, and federal, [...]

Not everyone in a hospital wears scrubs. Some, like hospital [...]

Social work explores complex systems with evidence-based practice to consider [...]

Career options for DSW graduates are bountiful and varied for [...]

Neuro-optometrists use neurology and optometry to understand vision and its [...]

Categorized as: Physical Therapy, Nursing & Healthcare