Education & Teaching - Career Paths & Degree Types

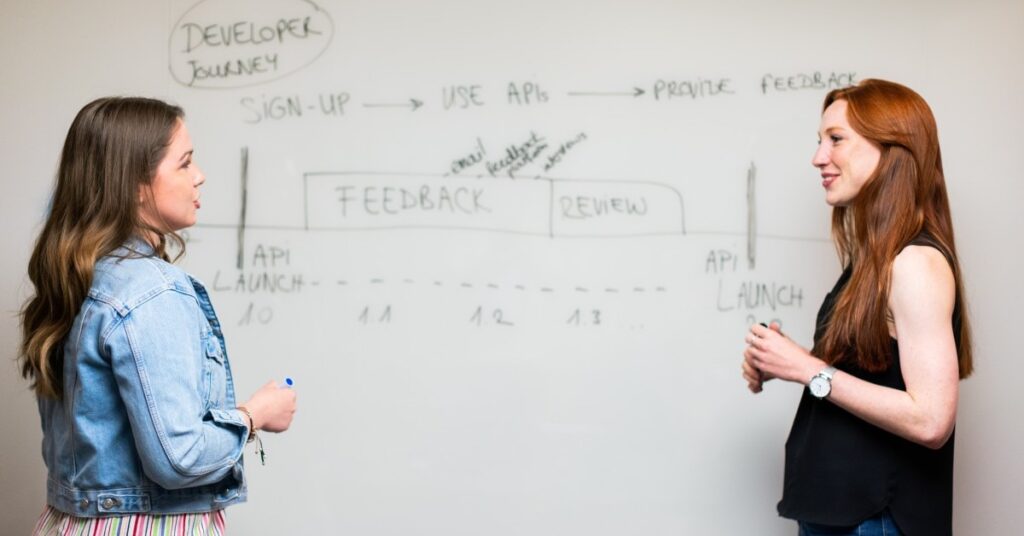

It’s never too early to start your education career. You can volunteer to assist teachers and tutor younger students while in high school. An associate’s degree or a bachelor’s degree in teaching or education can get you started professionally, while a master’s degree qualifies you for more advanced teaching, administrative, and policymaking roles—and a higher salary. Undergraduate teaching majors study the best pedagogic techniques, learning theory, and classroom management, while education majors supplement teacher training with explorations of curriculum design, school administration, and education policy. Many school systems require teachers to earn a master’s to acquire relicensure, typically five years after receiving their initial license. Even in states that don’t, educators benefit from master’s-level training that imparts subject expertise and advanced education skills and concepts. No matter what degree you need to advance in your education career, Noodle can help you sort through your options to find the one best suited to your needs.

Latest Articles

Boost Your Teacher's Salary with a Master's Degree

Article

Master's in Elementary Education Salary: How Much More Will You Make?

Article

What Do Math Teachers Earn in 2020?

Article

How Much Do School Principals Make?

Article

How Much Do English Teachers Make?

Article

How Much Do Music Teachers Make in 2023?

Article

How Much Can Kindergarten Teachers Earn in 2023?

Article

What Is a Master of Library and Information Science?

Article

Library and Information Science Electives

Article